We have moved our blog to Medium… please visit us at https://medium.com/lightspeedindia/ !

Before I joined Lightspeed, I was experimenting with five ideas that I wanted to pursue full time. Now that I’ve spent a good part of the last 1 year in the firm (or on the other side of the table at Starbucks Koramangala), here’s where I stand on them: 1) I would still pursue at least 3 of the 5 2) I would not seek venture capital for any of the 5. Here’s why: the interests I want to pursue have a niche following, not enough to build a multi million dollar business. Hence, neither do I think capital infusion will help me attain non-linear growth ($8 app install cost for users, 95% of whom will stay with me for all of 3 minutes), nor will it imply a large enough return for the VC firm backing me.

Diving into the mechanics: Assume a venture capital firm looking for a 10x return on an investment comes in at the seed stage, puts a million dollars for 10-20% equity. In the ideal case scenario that we are talking about, it invests ~$10M cumulatively in the subsequent rounds on a pro rated basis to defend its stake, also getting diluted when growth capital comes in, ending up at 10%. A 10x return implies a $100M return expectation, which means the company needs to be worth $1B. Calculating backwards, based on the enterprise value to revenue ratio (EV/Revenue) of analogous public companies, you can easily get a sense of the scale you need to potentially be at 5–6 years down the line to make a VC investor greedy.

Consider marketplaces as an example: Amazon has an EV/Sales ratio of slightly over 3, while for eBay this ratio is 2. Generally, an ecommerce marketplace would be valued at 2–3X its Gross Merchandise Value. So unless my marketplace company is selling over $300M worth of goods by end of year 5, it isn’t “impact potential” for the VC firm. Of course, this ratio varies by business model: Facebook trades at an EV of ~18X its revenue and Apple at ~3X. For consumer app companies like Facebook and Twitter that primarily monetize via ads, it might be prudent to look at the EV/user ratios. TL;DR – it’s critical to figure out what the model is, the implied scale it should attain and whether it seems reasonable in a 5–6 year timeframe, to ensure all stakeholders benefit in the long run.

Growing up in a milestone-oriented educational setup, we’re used to seeking incentives and rewards on a regular basis for comfort and reassurance. A full score on the weekly math test, 5 point reviews at work, we’ve always associated professional success with tangible tokens of appreciation. Of course, big companies aren’t built in a few months or even years. And if you’re the CEO, there’s little chance someone will give you a report card every few months. ‘Funding’ fixes this need for external validation. It becomes a proxy for success when in the truest sense, all it really should be is a lever for success. And that’s where a lot of us lose the plot. “What’s best for my business?” becomes “what’s most conducive to funding?”

It’s important to think big but it’s even more important to be honest with oneself. Does my business really need VC funding? Is this the right time? All good ideas don’t make for good businesses, and all good businesses aren’t necessarily venture backable. This is a great thread on some really successful companies that did not raise venture capital (Dell, Zoho, ESRI, SurveyMonkey), or delayed it until the business was sustainable enough and never needed to use it (eBay, Tableau, GitHub, Shopify). On the other hand, Gigaom that had raised $22M in 6 rounds is a recent example of a niche business that could have probably survived longer without VC infusion.

And hence, I will not raise venture capital when the time comes to do something of my own. My aspirations don’t lie in building a billion dollar company, they lie in doing something I’m passionate about (even if it has a limited, scattered audience — think investigative journalism, spiritual retreats, gourmet food tours!) while being able to draw an adequate amount of money every month. Oh, and the 100% ownership and decision authority is a bonus.

As published on Yourstory on August 5 @ Lightspeed-Oyo

Oyo is like a first baby to me. It is special. And the tale of how we discovered it is an interesting one. Oyo did not happen through the usual prospecting methods that VCs follow. It was rather serendipitous.

I love watching Sarah Lacy’s (PandoDaily) fireside chats. They throw insight into the mind of the entrepreneur/investor and tell inspiring stories. One late Saturday night, I logged onto YouTube to watch her conversation with Peter Thiel. During the chat, they talk about Peter’s ‘20 Under 20 Fellowship’programme. Peter is a strong advocate of young people choosing alternative paths instead of college education. Under the programme, Peter’s foundation grants USD 1,00,000 to 20 students who are under 20, to drop out of college and work on something revolutionary. I was intrigued by some of the examples (14-year-old kid building a nuclear reactor) and decided to learn more about these bold, visionary entrepreneurs who were doing amazing things instead of spending their time in college.

The current year Thiel Foundation fellows included two Indians. Ritesh was the only one doing something here in India. I reached out to him on LinkedIn and followed up with a Skype call as he was traveling to San Francisco.

The first conversation with Ritesh was mesmerising. Somewhere buried in Oravel’s introductory deck was the idea of Oyo. Oravel was a plain aggregator, much like an online travel agency (OTA), but Oyo was a fully integrated model that controlled customer experience right from discovery to booking, and all the way to the stay and check-out. This 19-year-old had traveled for months staying at budget hotels, attended customer calls everyday and immersed himself in every possible experience to learn about budget hotel customers and their expectations. That was the kind of on-the-ground learning that helped him pivot Oravel to Oyo. At Lightspeed, we gravitate towards entrepreneurs who build their consumer understanding bottom-up – Ritesh clearly stood out.

Subsequently, I arranged for Ritesh to meet Bejul, who was at SF as well at that time. Bejul had tracked the online travel sector for more than five years and met startups trying to connect travelers to budget hotels before. Internally, we had a point of view that a light touch aggregation approach is not likely the right one, given the nature of hotels in India. When he met Ritesh and learned about Oyo’s model, which had more control over the inventory and customer experience, he believed it to be the right answer. The fact that Ritesh had arrived at this conclusion based on his market experience and had the courage and conviction to pivot from the original model gave us important insight into his ‘learning orientation’, a characteristic we value highly in an entrepreneur.

We decided to spend more time with Ritesh and the team at Oyo to learn about the opportunity. Quintessential to Lightspeed’s diligence approach, we planned to experience, firsthand, the consumer experience at budget hotels.

That same weekend, I visited Mahipalpur – an area near the Delhi airport, which has about 50 budget hotels in a small stretch of less than two km. I knocked on the doors of eight to 10 hotels and pretended to be a medical representative who frequently travels to Delhi and is looking for reliable options at an affordable price. Learning from these conversations was mind opening in many ways.

On the demand side:

- It was extremely difficult for a consumer to gauge the experience “XYZ residency, inn” would offer. Reviews at Trip Advisor and/or pictures on OTAs would not solve experience expectation problem

- Pricing was completely arbitrary. Similar hotels at the same location would vary from Rs 1000 to Rs 2500 a night

- One could never be sure whether the booking will be honoured or not

On the supply side:

- There was a large pool of such hotels in the country

- It was clear that these hotels operated at low occupancy because of competition and a non-definitive/differentiated proposition. Also, they did not have a structured way of capturing demand

- Most of these hotels were not the primary business of the entrepreneur and a ‘general manager’, who usually took care of the day-to-day operations, had little incentive to increase occupancy

As I came out of Mahipalpur and watched the strip again, it finally dawned on me why an Oyo should exist for every 10 hotels in this strip. And if it did, the occupancy of the other nine hotels would gravitate towards the one Oyo, which is a national brand and one that people can trust. Today, there are more than seven Oyo hotels in the same Mahipalpur strip.

Bejul and I subsequently visited the three Oyos that were operating in Gurgaon and met their owners as well. A sleepy residential lane in Gurgaon had several of these budget-stay options, which further cemented our market depth thesis. It was also clear from our conversations with the owners that the Oyo model was working and that they therefore treated Oyo like a partner who has access to complete inventory rather than a marketing channel (e.g. OTAs). Interestingly, when we spoke to the OTAs, some of them did admit that this was a huge opportunity and they had themselves thought of capitalising on it. But it required a completely different organisation and it would be very tough to execute.

Oyo was still very young and in a state of transition:a few hotels and less than 10 people in the team, some of whom were part time and working from a different city. Ritesh and Anuj used to double up as call centre agents, business development executives and all that could possibly be there in the middle. We recognised that Oyo was in its cradle and would require enormous amount of company building. But our conviction in Oyo stemmed from our point of view of the opportunity, signs of early product-market fit, a belief in what the company could become and the clarity in Ritesh’s thinking and vision.

It has been an awesome rollercoaster ride so far. We are proud and fortunate to be a partner on this journey with Oyo, a startup that can truly claim that it is ‘disrupted in India’ unlike most models which become successful first in the West and then get copied here. Oyo for ‘X’ – primary care, diagnostics, schools, auto-service centres is quickly replacing Uber for ‘X’.

Oyo will celebrate its presence in 100 cities this month. It has a world-class team that strives to make it the largest network of technology-enabled hotels in the world. Ritesh is now 21, a dreamer who operates with clarity of purpose, speed and conviction that is a defining trait of successful entrepreneurs.

Watch out for the next post in this Oyo blog series ’How Oyo built a world class team’

[Published on YourStory.com]

[Published on YourStory.com]

This week Craftsvilla announced a Rs 110 Cr round led by Sequoia and supported by existing investors Lightspeed and Nexus and new investor Global Founders Capital. This is an important milestone for a company that has quietly been building out India’s largest marketplace for ethnic apparel and products.

In our view, Craftsvilla stands out from the majority of e-commerce companies for a few reasons:

– It has broken into the top-5 ecommerce companies in India by GMV scale

– Has grown 4x in scale in the last six months (and continues that trajectory)

– It turned the corner on cash flow breakeven while achieving such scale and growth

All this, on the $1.5M that the company cumulatively raised from Lightspeed and Nexus across its seed and Series-A rounds in 2011 and 2012. This performance is exceptional by all standards and is driven in essence by two key factors:

A. A fundamentally strong business model: Craftsvilla is going after the massive ($30B) market of ethnic apparel and products in India. This market is highly fragmented across a very large supplier base and thus needs a specialized vertical player to go after it. Since the supplier base is fragmented, it takes longer to build liquidity on the platform but once the critical mass of buyers and sellers are live on the platform, then the margins are attractive and entry barriers are very high. ETSY solved a similar problem for the US market and is currently valued at $2.8B post its recent IPO. Craftsvilla has gone through the hard part of getting the platform to scale and the quality of the current business is reflected in several metrics:

- Marketing spend has stayed below 10% of sales while revenue has grown 4x in last six months

- Organic sources contribute two-thirds of the total traffic

- An active seller base of 12K artisans who by themselves upload and manage an inventory base of 2M SKUs on the platform

- High fragmentation within the seller base: Median contribution of top-10 sellers to GMV is 1.5% and beyond top-10 no seller contributes more than 1% of sales.

B. Extraordinary perseverance and focus of the founders: There has been a frenzy of ecommerce funding in India. Instead of going down the path of driving GMV through discounting and at the cost of margins, Manoj and Monica went through the harder path of building the core of the business – bringing thousands of suppliers across the country on to the platform and helping them sell online. To continue to do this for multiple years while the industry was rewarding a capital led growth path needs strong founders with deep conviction. It is always helpful to look back at certain ‘forks in the road’ and learn from the experience. The team made a number of critical decisions with crystal clear conviction that, in hindsight, worked well for the company. These include the following:

- A clear commitment to being a marketplace vs. a retailer (or mix of the two)

- With this clarity, focused aggressively on aggregating sellers and building strong technology-led capabilities to on-board sellers and allow them to sell through the Craftsvilla platform

- Letting the diversity of supply drive demand instead of using a discount led approach

- Kept the team lean and fixed cost burden low: Manoj and Monica gave it everything they had and built a young and highly motivated team around them – a team of 15 people till a couple of months back! Conventional wisdom might have argued for a seasoned and pedigreed team that allows for accessing capital faster.

When Lightspeed, along with our partners at Nexus, made the seed investment in Craftsvilla back in 2011, we were struck by the founding team’s passion for, and understanding of, the market opportunity as well as more measurable factors such as market size, the potential for attractive unit economics and the scope to build a differentiated company that the horizontal e-commerce platforms would not be able to easily replicate. We also believed that this was a powerful opportunity to leverage the internet to unlock new markets within India and globally for artisans and vendors who, until then, were only able to serve their local customer base.

As the company looks forward, there remains much work to do – from iterating on product to building company leadership and replicating the platform in similar markets globally. They can do this with the very strong foundation of capital efficiency and product-market fit that has already been built. We are fortunate to be associated with the company and look forward to being a part of this journey with Manoj and Monica.

Also read Manoj’s post on how the Craftsvilla team created this magic.

Copyright Lisa Clarke

There has been a lot of chatter on the Internets about unbundling of mobile apps. Tech media’s interest has been piqued by some larger brands jumping onto this bandwagon – examples include Microsoft, Twitter and Foursquare.

It’s not a new strategy. Featurephone apps companies used this for a long time. Several smartphone app publishers have had an owned & operated network of apps right from the beginning – examples include Zynga, King, Supercell, Smule and Outfit7. Incumbent media companies like CBS, News Corp, Viacom, Time Warner, Walt Disney and (in India) Times Internet have also had these networks for a while. Established Internet companies like Facebook and Google have had networks, built organically and through acquisition.

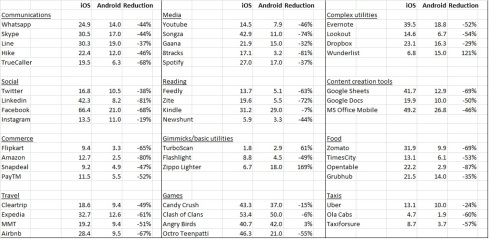

I think unbundling is a strategy that has not yet been applied with vigor in the emerging markets on smartphones. I think there are potentially disproportionate advantages to be had by unbundling in countries like India, in the short- to medium-term. Why is this? Because low device memory limits (typically less than 16 Gb), low bandwidth limits (mostly 2G) and relatively high bandwidth prices result in dramatic drops in conversion rates, download success rates and retention rates as app size increases. Also, in my opinion, discovery on the app stores is easier when there is a single focused value prop (kind of the approach that Whatsapp has taken with a singular focus on messaging).

Conversion rates drop with package size. Below is data from a global mobile analytics and advertising vendor. Data is global and is an average across all advertising products.

| App Size | Conversion rate |

| 0-5MB | 1.00% |

| 5-50MB | 0.80% |

| 50MB+ | 0.42% |

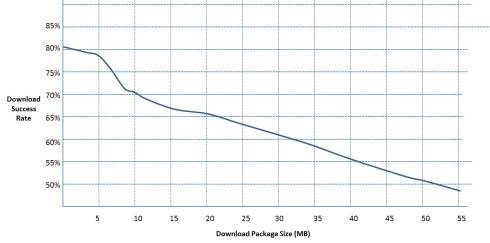

Download success rate is nowhere near 100% (even on Android). The graph below is from China. I would imagine that the drop-off in India is steeper, given the greater prevalence of 2G and higher proportion of lower-end phones.

Retention rates drop with larger file size. Large apps are 33% less likely to be retained after 1 month although iOS users are 12% more likely to retain an app than Android users, according to Flurry.

App sizes vary by app type and platform. Below is some data I gathered from the iOS and Play stores. Basic utilities are 1-10MBs. Communications and social media apps are 20-30MB. Most casual games are 40-50MB. Most mid-core games are 300-800MB. From my not-so-scientific sample list below, Android apps are on average 37% smaller in package size than the iOS app from the same publisher.

So, what is an ideal app size, especially in markets like India with challenged infrastructure?

The ideal size is 10-15MB globally. Idea size for an app for tier 2/3 countries (like India) is below 5MB. 500MB+ is a non-starter. At 50MB+ the conversion rates fall off dramatically. On Android and iOS, conversion rates dip by 50% in tier 1 nations for non-game apps above 50MB. In tier 2 and tier 3 nations, conversion rates dip by 50% for games above 15MB.

To lower the cost of loyal customer acquisition (a function of conversion rate, download success rate and retention rate), unbundling in emerging markets makes positioning more clear and therefore discovery is easier, in my opinion. Unbundling also decreases the hits-driven nature of mobile apps businesses. And finally, cross-promotion within an owned & operated network of apps also dramatically reduces the cost of introducing a new app into the app network.

There is a cost to this strategy though. The engineering and products team now need to maintain multiple code-bases and roadmaps. Initially building out the network may required multiple marketing pushes and already strained marketing budgets may not be enough to get apps into into the high ranks on the app stores. Unpopular functionality, separated out into an app, will not get downloaded/used.

Some things to keep in mind if you are thinking about going down this route: You need to maintain a strong brand identity across all apps in the network to build company value and cross-promotion ability. Also need a common ID system to build and leverage customer data across multiple apps. And a good cross-promotion engine is needed. Tapjoy and Flurry are leaders in this category but there are lots of other options. To reduce app package size, you will need to rationalize your third-party SDKs, remove most heavy media files and reduce functionality dramatically.

[Published on Yourstory.com]

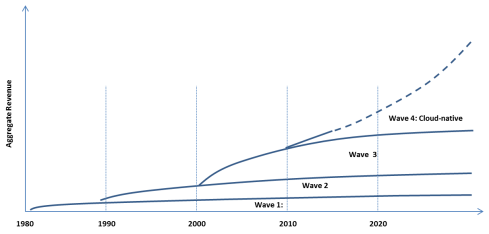

India’s enterprise software industry has been slowly bubbling since the 1980s but has generally failed to deliver a large number of high impact, high value companies. We do have some companies that everybody talks about – iFlex, Tally, Zoho – but these are far and few between. I believe that we are seeing a new scalable wave of enterprise software companies coming out of India and there is a potential to deliver several high impact companies over the next decade. Here at Lightspeed Venture Partners, leveraging our global strength in enterprise technologies, we see opportunities to partner with companies that are cloud-native and have cracked a global market – examples of current active categories in India are CRM, analytics/big data, marketing automation and infrastructure.

India’s enterprise software industry has to be looked at separately from the outsourcing/BPO firms like Genpact, Cognizant, Tata Consulting Services and Infosys. Starting in the 1980s and early 1990s, this services industry is now mature and at scale.

Separate from the outsourcing/BPO industry, India’s enterprise software industry (or “products” as it is called by many here in India) has evolved from the 1980s to now in what I think can be divided into four waves, coinciding somewhat with three trends: 1) enterprise software moving from desktop to client-server to cloud; 2) evolution of Indian industry post 1991 liberalization; and 3) increased experience of Indians at successful US product companies.

WAVE 1

The first wave of software products came along in the late 1980s/early 1990s – the focus was desktop products for business accounting. Companies in this wave include Tally Solutions (still the undisputed leader in SME accounting software in India), Instaplan, Muneemji and Easy Accounting.

WAVE 2

This generation of software products emerged in the 1990s as projects within outsourcing firms or from internal services arms of larger corporates. Infosys launched Finacle. Ramco Systems launched its ERP. And Citibank launched CITIL which became i-Flex. Other notable companies included 3i Infotech, Cranes Software, Kale Consultants, Newgen Software, Polaris Financial Technologies, Srishti Software and Subex.

I remember attending CEBIT in Hanover in 1989 when many of these Indian software and consulting companies were first introduced to Europe.

Did you know? Year 1989, the first time CeBIT introduced the concept of a partner country. Our first partner? India! pic.twitter.com/9sWx68Yzmp

— CeBIT India (@cebitindia) February 13, 2014

The late 1990s saw a wavelet of ASP (application service provider) startups in India, most of which got crushed after the dotcom bust.

WAVE 3

![]()

The 2000s saw on-premise India-first companies such as Drishti-Soft, Eka Software, Employwise, iCreate Software, iViz, Manthan Systems, Quick Heal Technologies, Talisma (for which I did some initial product management work while at Aditi Technologies) and Zycus get started. This was the era of 8-10% GDP growth in India which lasted till about 2010. Many of these companies had a direct sales model. After India, they generally expanded into the global South (Africa, Middle East, SE Asia, Latin America) where they found similar customer requirements and little competition from Western software companies. Bootstrapped in their earlier years, some of these companies grew over several years and have broken through to $25 million+ in annual revenue. Key verticals have traditionally been BFSI (banking, financial services and insurance), telecom, retail/FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods aka CPG in the US) and outsourcing/BPO.

Having been around for over a decade, some of these companies generally face the challenge of migrating to the cloud, upgrading user experience to modern Web 2.0 levels, and expanding addressable markets beyond the global South to the US and Europe. We have seen some of these companies get venture funded, typically at much later stages in their go-to-market relative to US-based software companies. Several of these companies have received funding in the past couple of years, ostensibly to “go international” and “go cloud,” not an easy task, especially when done together.

WAVE 4

Starting in around 2010, a new wave of cloud-native companies were launched, perhaps following the slowdown in India’s economy and the growth/acceptance of SaaS as a delivery model and as a sales model in the US. These companies have grown and now could power beyond the $10M/year revenue glass ceiling. The reason for the scale potential being higher for this cloud-native wave is the cracking of efficient online sales channels to reach markets globally.

Why this decade? Because there is an increased willingness of companies around the world to search for and buy software products online. There is now a large pool of founders who have worked at global enterprise product companies (e.g. Indian offshore development centers or in Silicon Valley itself with companies like SAP, Oracle, Google, Microsoft, Adobe) and have experience in product management, marketing and sales. And finally, there has been a dramatic reduction in the capital required to bootstrap enterprise software companies. Everybody uses AWS and software from other startups to get started. It’s quite meta.

Wave 4 companies have the opportunity to break through the barriers that previously relegated Indian enterprise software companies to selling to the global South. We have seen Atlassian (Australia), Zendesk (Denmark) and Outbrain (Israel) do this move to Western or global markets. Zoho is an Indian company that is rumored to be at $100 million per year revenue scale – they have been part of many of the waves I have described.

This cloud-native wave, I believe, can be divided into two dimensions. One dimension is the platform/tools companies versus workflow automation (applications) companies. The other dimension is India-first companies versus the global-first companies. We see opportunities in all four quadrants, each having its own challenges. We are interested in looking at companies in all these segments, with a bias toward companies which have reached some scale ($1M ARR) and are going after large addressable markets with aggressive sales & marketing execution.

| Applications | Markets: Enterprise (retail, banking, telecom, BPO, ecommerce) Examples: Capillary, Peel Works, Wooqer, Sapience Categories: Employee productivity, verticalized ————————————————— |

Markets: SMB/mid-market Examples: Framebench, Freshdesk, Kayako, MindTickle, Unmetric, Zoho Categories: Mature SaaS segments eg CRM, SMM, horizontal ————————————————— |

| Platforms/ Tools | Markets: IT dept, developers, SMB, media Examples: Exotel, Knowlarity, Germinait Categories: Telecom infra, app dev tools ————————————————— |

Markets: IT dept, developers Examples: Browserstack, FusionCharts, Little Eye, Mobstac, Webengage, Wingify Categories: app dev tools, marketing automation, security ————————————————— |

| Model: License+AMC, direct sales, resellers | Subscription, telesales, online sales (SEO/SEM,content mktg) | |

| India-first | Global-first |

[Please note this is not a comprehensive list of companies nor a view on which companies we admire or not]

Global-first companies coming out of India have started to crack or have cracked the online sales model, using SEO, SEM, content marketing and telesales. They are typically going after mature segments where buyers are typing keywords into Google at a high rate. This online selling model results in an SMB and mid-market customer base. In many cases, founders may have to move to the US to pursue direct enterprise sales. It’s worth noting that scale markets are not necessarily all in the US – companies could get built with a general global diffusion of customers, perhaps with help from resellers.

I see India-first companies typically going after newer high-growth companies in India (e.g. ecommerce, retail) and startups. Some go after Indian arms of multinationals (MNCs). This is a reasonable early adopter market to cut a product’s teeth on, but has limited ability to scale. Of the newer crop of India-first companies, very few go after large enterprises in India – there are exceptions like Peelworks and Wooqer. The model here generally is SaaS as a delivery model but not SaaS as a sales model (ie direct sales, not self-service). Many software companies are essentially verticalized.

We continue to see a few high-ticket, high touch direct sales enterprise software companies which are global-first, including companies like Cloudbyte, Druva, Indix, Sirion Labs and Vaultize. Many of these start out with teams in both Silicon Valley and India or transplant themselves to the Valley over time. I think this will continue to happen but we will not see the explosion here that we are seeing in the number of companies utilizing low touch online sales models. I see several high-impact companies coming out of these direct sales enterprise software startups as well.

I think this dichotomy between India-first and global-first companies is interesting and makes India a distinctly different type of investment geography, different from Israel (which has very small domestic market where tech companies move to the US very quickly), different from China (which mostly has domestic market focused startups and very little enterprise software) and different from the US (which is primarily domestic-focused in $500B enterprise tech industry in the early years of most startups). In terms of investor and founder interest, the pendulum may also swing back and forth between these two models as the Indian economy grows, sometimes at high speed, sometimes at a snails pace.

[With input from the team at iSPIRT and several of the companies mentioned above].

[Published in NextBigWhat on May 19, 2014]

[Published in NextBigWhat on May 19, 2014]

This blog post illustrates how products have used comparison and choice based user interactions to successfully reinvent consumer experience on mobile. The underlying concept is titled ‘Hot’ or ‘Not’, derived from the original website created by James Hong. ‘Hot’ or ‘Not’ is now used by many products including an accidental creation from an entrepreneur we all know very well.

Remember Facemash? – Facebook’s predecessor that asked visitors to choose between pictures of students placed side by side and decide which one was ‘Hot’ or ‘Not’. Facemash may have been a product of Mark’s intoxication…a joke…an experiment if you will. But as I see it, it could very well be a great product concept that can wow the consumer and exponentially increase engagement, especially on smart-phone devices. To illustrate this thought, let’s look at a few examples.

Tinder is a dating platform, which has used this concept and has been hugely successful. It lets you swipe ‘Liked’ or ‘Nope’ on images of women and men located close to you. So rather than answering a million questions on ‘Okcupid’ or ‘Match’ and relying on intelligent algorithms built by MIT/Stanford data scientists (who apparently understand dating), you just swipe on Tinder and get connected to people who have swiped ‘Liked’ for you as well. Simple, fun and it works!

What makes Tinder great and gives the application of ‘Hot’ or ‘Not’ credibility is the fact that it is absolutely frictionless. It connects people easily and instantly. Currently, Tinder gets 750 million swipes a day and makes more than 8 million matches. As compared to it, Okcupid, which is one of the most successful dating platforms, has 1 million daily users. Hence, far less matches when compared to Tinder.

Thumb is an app that lets you get or give opinions in real time. From asking people about their travel destination choices, to product preferences all the way up to soliciting opinions on love lives, Thumb transcends a host of categories. It quickly became an addition and a community before it merged with Ypulse. Though Thumb was not as successful as Tinder, it does represent the kind of exponential engagement ‘Hot’ or ‘Not’ type products concepts can derive.

Thumb reminds me of a show called “kaun banega crorepati” – the Indian version of “Who wants to be a millionaire?”, where the contestant can use a life line called the “audience poll” if he/she is unsure of the answer. And there are plenty of such situations, which are frequent in nature, where we need advice and we would rely on wisdom of the crowds rather than make the decision ourselves. Hence, presumably Thumb’s success was because the ‘Hot’ or ‘Not’ type product concept was applied to a simple real life problem encountered by every man and woman almost on a daily basis!

‘We heart it’ is an image based social network that has quickly grown to over 30 Million users serving 50 billion images per month. Users ‘Heart’ images that they love and put these images in their collections that are shared with their friends and followers.

‘We heart it’ is incredibly simple, yet a very powerful way for people, especially teens to express themselves – their personalities, feelings, preferences, opinions through images. Images based networks have existed for long (remember Flickr?) but they never achieved the kind of scale ‘We heart it’ has done. Secret to their massive and instant success – a simple application of ‘Hot’ or ‘Not.

Fad or science?

It is easy to pass this as a quirky fad. However, the concept of ‘Hot’ or ‘Not’ has deep routed scientific reasoning. For those who are familiar with market research techniques, would know Conjoint analysis to be a bedrock of research studies. The simple form on conjoint analysis asked consumers to rate and review products just like a lot of platforms on the web today. This was disrupted when CBC or Choice based conjoint came along and proved to be a much better alternative. CBC asked consumers to choose between different product or service concepts and say whether it is ‘Hot’ or ‘Not’. It was argued by scholars that CBC works well because that’s how human psychology works. It is natural and intuitive to choose, it is unnatural and much more difficult to rate. Also, the variance or the error in the latter was higher. For the curious souls, you can read about CBC here

‘Hot’ or ‘Not’ for Indian start-ups

Mobile is key to the growth of Indian start-ups. The mobile user is on the go, wants to be quick and fluid with his/her interactions with the device, does not like typing and is more visual. These aspects make it imperative for Indian start-ups to re-imagine their products for the mobile. Traditionally –

– Mobile products have been replications of web interfaces including the feature set and the sequencing of the user interactions

– The platform is not built around a single user input like a Pin, Thumb, Heart or Fancy. Instead, it is cluttered and asks users to do multiple things. For e.g. several buttons beneath an image asking the user to Comment, Like, Share and more.

This is where concepts like ‘Hot or ‘Not’ could help achieve a wow consumer experience and quick scale. – just like the examples illustrated in this post have done. Perhaps, soon we will see E-commerce sites moving to ‘choice’ from ‘browse’, Review/rating platforms giving up the age old 5 point rating system and new-age dating/marriage platforms innovating like Tinder.

If you think this article was ‘Hot’, feel free to write to me at maninder@lsvp.com and/or visit the Lightspeed blog to leave a comment…Or just ‘Digg’ it.

I am looking forward to attending iSpirt’s Intech50 event next week in Bangalore. Fifty Indian enterprise technology companies will be there, meeting with fifty CIOs from the US and India. Congrats to everybody at iSpirt, including Sharad Sharma and Avinash Raghava, for organizing what promises to be a productive spot-market.

We have put the names of the Intech50 companies into a list and categorized by tech category (applications, infrastructure, tools), vertical (e.g. none, financial services, retail) and geographic focus (India, India->Emerging Markets, India->Global, Global). See the Slideshare embed below to view or download the document. Perhaps this is of help to you while navigating the Intech50 event.

These companies are two-thirds infrastructure, one-third applications. Analytics and security dominate the categories, followed by HR and CRM. A good 75% are horizontal solutions while the rest are verticalized. And more than half have a global go-to-market while about 40% are focused on India or adjacent markets.

The last decade, especially the past five years, has seen a lot of change for the better in the enterprise tech startup market in India. Startups have started building world-class product and user experiences. They have understood how to leverage online marketing to acquire customers outside India, versus relying on channel partners in other countries or sticking to just the India market. They have figured out how to initiate direct sales abroad, not relying on hiring expensive VPs of Sales as a first step but sending founders abroad to kickstart sales. They have started efficiently selling into the long-tail of companies rather than just focusing on large enterprises. And they have taken full advantage of platforms such as AWS, Force.com, etc. to run and distribute their products.

I think there is a clear progression forward from the types of enterprise software companies started 7-15 years ago which many times started with services projects; were usually vertically focused on banking, telecom or retail; and, despite branching out to SE Asia, Middle East and Africa, have generally tapped out growth at the sub-$10M annual revenue mark. There were exceptions of course, including companies like I-flex, Subex and Ramco.

Lightspeed globally has put a majority of its capital to work in enterprise technology companies, represented here. Many of our portfolio companies, including Qubole, Numerify and Bloomreach, have teams in India. In India, we are looking for enterprise technology companies that can be category-defining and category-leading and can scale to $50-100M in revenue over time. We are finding higher than average growth coming from applications companies focused on a global or US go-to-market – examples in India would be Freshdesk and Unmetric. We are also seeing such growth from globally-focused infrastructure and developer enabling technologies – examples in India would be Druva, WebEngage and HelpShift.

See you at Intech50! Come talk to us. You can reach me at dkhare at lsvp dot com.

Lightspeed is excited to announce that the firm has led the first venture round in

Lightspeed is excited to announce that the firm has led the first venture round in

This morning, LimeRoad announced

This morning, LimeRoad announced

Comments